Editor’s note: Over the next several weeks, Tysons Reporter is profiling the eight districts of Tysons. This is the first article in that series.

Tysons Central 123 is the commercial heart of Tysons. Residential towers, tree-lined boulevards of storefronts, and perhaps a convention center will catalyze the continued success of this retail district as the Tysons Comprehensive Plan is carried out.

Tysons Central 123, named after Route 123, contains over half of Tysons’ retail floor space. Almost all of that retail is concentrated in the two enormous malls that define the neighborhood: Tysons Corner Center, south of Chain Bridge Road, and Tysons Galleria, north of it. Combined, they make the district a regional shopping destination.

As it stands, Tysons Central 123 is a major shopping destination — but very little else. That was a successful approach when Tysons was only a suburban mall, but now changes are in the works.

The district’s section in the Tysons Comprehensive Plan calls for it to evolve into a full-fledged neighborhood. That means tree-lined boulevards rather than congested highways, it means mid- and high-rise buildings rising around the malls, it means more retail at street level, and it might mean a convention center.

Fifth Avenue in New York isn’t only a shopping destination. It also offers cultural destinations, a pleasant outdoor streetscape, and a large residential community. All of these will increasingly appear in Tysons Central 123, supplementing the shopping rather than detracting from it. Retail will continue to define the neighborhood.

“This district is envisioned to remain the region’s signature shopping destination,” states the Comprehensive Plan.

Hills and Valleys

One particular feature of the Tysons Central 123 district is the steep topological slope down from Tysons Drive to Westpark Boulevard. Planners see this challenge as “an opportunity to integrate the district with the adjacent North Central District” through “terraces and plazas” that could provide a unique character to the surrounding neighborhood.

Getting Around

Today, the area has strong transportation options: the Tysons Corner station of the Silver Line anchors the center of the district. The transit center there is served by eight different bus lines, more than any other point in Tysons, connecting to destinations near and far. However, with increasing density, existing challenges for mobility will become more pronounced.

Northern Virginia is home to an astonishing variety of native species of trees and shrubs, and now you have an opportunity to grow your own.

Fairfax County’s annual Native Seedling Sale will be taking place today, Friday April 5, from 9 a.m.-4 p.m., and tomorrow, Saturday April 6, from 9 a.m.-noon. The event will be held at the Sleepy Hollow Bath and Racquet Club, at 3516 Sleepy Hollow Road in the Falls Church area.

Note that the pre-sale period has ended, so there’s no guarantee that the plant you want will be available — or even that any plants will. However, the county website states that “We often do have extra packages or individual seedlings for sale on the pickup days (April 5 and 6).”

This annual sale helps local residents beautify their gardens with indigenous plant species that “help cleanse water, prevent soil erosion, provide habitat, cool our climate and clean our air.”

This year’s theme is “Incredible Edibles,” so be prepared for plants that delight the tongue as well as the eye.

The plants include seedlings of pawpaw (Asimina triloba), a tree native to a wide swatch of the greater Appalachian region. It bears a delicious fruit which was recently highlighted by National Public Radio’s The Salt as “the hipster banana”.

Other selections include the American wild plum, the American elderberry, the black chokeberry, the American Hazelnut, and the flowering dogwood (Virginia’s state tree).

The packages cost only $12.50 or $17.50, depending on contents, and are easily transportable in a car — though the organizers recommend you bring a small bucket, basket, or doubled-up paper bag.

Map via Google Maps

Northern Virginia boasts the state’s first modular roundabout — a new traffic management technology that could become part of everyday life in Tysons.

Drivers venturing out to Annandale might have noticed something unusual at the intersection of Ravensworth Road and Jayhawk Street. This avian-named crossing is home to Virginia’s first-ever modular mini-roundabout, a new type of intersection design that could see much more widespread use across the region, including in Tysons.

Before last May, the intersection had only had stop signs on Jayhawk. But traffic was increasing, and cars turning from Jayhawk onto Ravensworth were having to struggle to turn enter the road safely. The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) decided they needed to do something to keep cars moving.

“The primary purpose of the roundabout was to allow side streets to have safer access onto the main road,” explained Terry Yates, Assistant Transportation and Land Use Director for VDOT in Arlington and Fairfax Counties. The goal was achieved: the time that cars spend waiting to turn onto the main road has dropped by almost 90%.

They could have installed traffic lights, which would probably have cost around $600,000. Or they could have installed a conventional concrete mini-roundabout, probably around $300,000. The concrete mini-roundabout would have both been safer for pedestrians and minimized the effect that pedestrians have on vehicle traffic compared to a full-scale roundabout or a traffic signal. Dr. Wei Zhang, researcher for the Federal Highway Administration, noted that the roundabout design (whether modular or concrete) “cuts down the exposed crossing distance for pedestrians by 75%.”

For a long time, those were the only choices. But the new modular mini-roundabout is unique because it is made out of a special plastic rather than concrete. That gives it a number of enormous advantages.

First, it brings down the cost — tremendously. This design cost only $137,000 of VDOT money, although it would have been a little more expensive without materials donated by the Federal Highway Administration.

Second, installation is easy. Setting up the intersection took only two weeks, slightly less than a comparable non-modular project in Vienna. There were no impacts on utility lines or right-of-ways, and only minor impacts to the pavement.

Third, it’s eco-friendly. The plastic material is made from recycled milk jugs, reducing not only costs but also pollution. That environmental friendliness doesn’t come at any kind of cost to effectiveness: the material in question is durable and strong enough that it’s used industrially for railroad cross-ties.

The design is still experimental. In fact, the first such modular mini-roundabouts anywhere in the country were only built about two years ago in Georgia. As such, VDOT is keeping a close eye on the project. Yates explained: “We are monitoring it about every 4 months. We discuss its performance with Fairfax County Police, Fairfax County DOT, Fairfax County Government and internal VDOT sections.”

The solution isn’t perfect: VDOT has yet to develop a snow-removal procedure, and some drivers complain that the design is difficult to see at night.

Although the roundabout was built to be easily removed, Yates clarified that it “may not be temporary.” If the design continues to function as effectively as it has for the past ten months, there’s no reason it shouldn’t stay as it is — and no reason why it might not be emulated elsewhere, especially in Tysons.

In Tysons, VDOT owns and maintains most roads, meaning they could easily replicate this success. Dr. Zhang has said that “transportation departments may be able to consider similar modular roundabouts as an option where safety and congestion improvements are needed quickly.”

With Tysons slated to grow to 100,000 residents and 200,000 jobs in the next thirty years, this cheap, safe, effective intersection design could be coming to local streets in the near future.

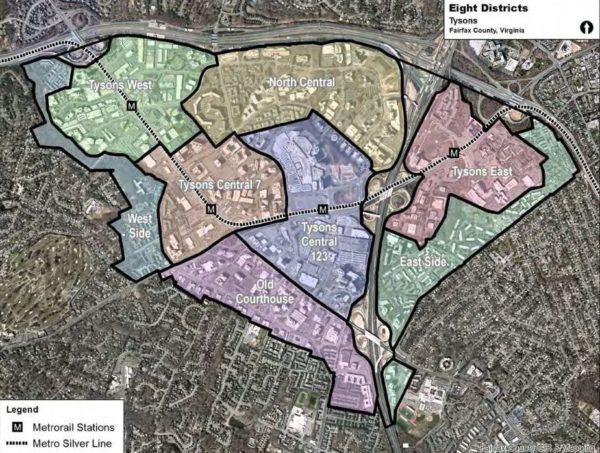

Tysons is larger than many people realize.

The triangular area under Fairfax County’s Tysons Comprehensive Plan extends from Magarity Road in the east to Raglan Road Park in the west, with its southern tip just north of Marshall High School. That’s about 3.3 square miles or 2,100 acres — larger than the area between the Lincoln Memorial, Union Station, and the Wharf in D.C.

It’s difficult to even talk about such a large area, much less plan for it, as a single entity. D.C. has its famous quadrant system, Paris has its twenty arrondissements, and Tysons has eight districts.

Fairfax’s award-winning 2010 comprehensive plan for Tysons is clear that “the transformed Tysons will be organized around eight districts, each with a mix of land uses.” That is to say, these aren’t zones that each exclusively focus on one activity — rather, each district will include residences, workplaces, shopping, recreation, and civic centers. Ultimately, the vision is for eight neighborhoods, each one supplying everything needed for daily life.

The planning for these districts also envisions specialities for each one, emphasizing different ways they can contribute to Tysons’ urban mix. No neighborhood will be a single-use zone, but they will nonetheless have certain specialties.

Visually, the districts are simultaneously continuous and distinct. Although there are clear boundaries on a map, those boundaries won’t be apparent in reality.

“Each district will be connected to the others,” the plan says. “Boundaries between the districts will be blurred as people move seamlessly from one place to the next.”

These eight districts have their own identities. The comprehensive plan “encourage[s] design elements that highlight the distinct character of each district,” largely through parks, plazas, and other public spaces but also through streetscape design, architecture, and land uses. In the same way that Capitol Hill and the Washington Navy Yard feel clearly different, planners hope that each neighborhood of Tysons will be unique.

It’s worth noting that, although Fairfax has provided provisional names to the neighborhoods, they’re not always the most user-friendly — and the county “may consider modifying the district names” as identity formation progresses.

In a series of upcoming articles, linked as they become available, we’ll examine each of the districts in detail. For now, we’ll leave you with a quick overview.

Transit-Oriented Districts

The first four of the districts each correspond to a station on the Silver Line. These districts, combined, are expected to account for 75 percent of future development and “will resemble intense and busy downtowns.”

- Tysons West and the Spring Hill Metro station will welcome those arriving from Reston and beyond. It is “an optimal location for an arts and entertainment district, including restaurants and entertainment options that stay open after the workday ends.”

- Tysons Central 7 and the Greensboro Metro are envisioned as business-focused, with a high concentration of office space, but also “a civic center with a mix of public, residential and commercial uses.”

- Tysons Central 123, with two malls and the Tysons Corner station, is and will remain “the region’s signature shopping destination.”

- Tysons East and the McLean Metro station will be the eastern gateway of Tysons, defined by Scott’s Run, which is “envisioned to transform into a great urban park surrounded by mixed use development.”

Non-Transit-Oriented Districts

The four remaining districts are farther from Metro stations and are envisioned as transition zones leading into the nearby neighborhoods. They contain some “areas that should maintain their existing characters, uses, and intensities.” However, just because they’ll be less dense than the preceding four doesn’t mean they won’t be urban — most of these areas are already as dense as much of D.C. and most lie within a 10-15 minute walk of Metro.

- The West Side will continue to be a primarily residential neighborhood, with natural amenities and close proximity to the Metro corridor.

- Old Courthouse, in the southwestern part of Tysons, is expected to develop a wider range of neighborhood-serving retail and restaurant options while it functions as a transition zone between the core of Tysons Central 123 and the surrounding residential areas.

- North Central, sandwiched between the Dulles Airport Access Road and the center of Tysons, is expected to see the continuing development of urban neighborhoods like The Mile.

- The East Side, with investments in connectivity like a pedestrian bridge over the Beltway, will form a primarily residential community smoothly connecting Tysons to Pimmit Hills. These residences will be supported by local retail and live-work opportunities.

The crossing of Chain Bridge Road and Leesburg Pike — where Mr. Tyson’s fruit stand stood eighty years ago — could soon see some major changes.

Right now, that intersection is an elevated partial cloverleaf interchange, the way it’s been since at least 1980. But it could become a new kind of intersection and a new kind of public space.

A few years ago, Tad Borkowski of the Fairfax County Department of Transportation was assigned to study the possibility of widening Leesburg Pike (Route 7). He found that the existing interchange would prevent that from ever happening: the tunnel under Chain Bridge Road (Route 123) was too narrow to ever accommodate a wider passage, he told Tysons Reporter.

The interchange had another problem, too. It wasn’t in its natural environment. It had been constructed for a much more rural place — at the time, most of the area considered today to lie within Tysons’ eight districts was still forest.

Now, Tysons has urbanized. Routes 7 and 123, which were once freeways, have been bogged down in a series of traffic light intersections on all sides of the interchange. The traffic bottleneck is no longer that crossing; now, it’s the rest of Tysons.

That means that the traffic efficiency gained by a partial cloverleaf is pretty much lost anyway — it doesn’t do anyone any good to cruise through the interchange when they just hit a red light at International Drive right afterward.

Also, as Tysons urbanized, land became much more valuable. In the 1970s, that land was cheap to build ramps on. Now it has higher and better uses.

Burkowski’s office has started to look into improved set-ups for the intersection. Specifically, they’ve focused on two possibilities — a “two-quadrant” option and a “continuous flow intersection” (CFI) option. There are some technical differences between the two, but they both amount to the same basic idea. They both give drivers a way to take left turns without blocking oncoming traffic, which dramatically increases throughput. This YouTube video gives a quick, intuitive explanation.

Burkowski examined both possibilities for the intersection under simulated conditions for the year 2050, assuming a denser grid of surrounding streets (this dense, urban grid is a critical element of the Tysons Comprehensive Plan) and increased numbers of vehicles — but not considering the possible effects of autonomous vehicles.

Both options provided very similar traffic throughput results. Both options also provide opportunities for constructing a bus rapid transit line along Route 7 through the intersection, in keeping with ongoing plans.

The two-quadrant approach takes up a wider space — though still smaller than the existing interchange — but offers some advantages in pedestrian safety by allowing people to cross the intersection step-by-step.

As Tysons becomes more and more dense, pedestrian mobility is increasingly valuable. Burkowski, though, is confident: “We don’t want to mix pedestrians and cars at all.”

First, at speeds like those on these major arteries, the road simply is never a safe place for a human body. Second, including a pedestrian phase in the traffic signals would slow car throughput to unacceptable levels. Finally, third — there is an alternative.

The Fairfax DOT is considering the concept of building pedestrian space over the new intersection. Because there won’t be any vehicle ramps, cars will stay at ground level – letting pedestrians take the air above them.

This pedestrian space could be a lot more than just a bridge. Prioritizing connectivity, it could be a cap, reaching all across the intersection and converting it into park space – even into a kind of “central park” for Tysons. It could also be a series of bridges with an elevated central plaza, connecting not only to the four corners of the intersection but also directly to the Greensboro Metro station only 800 feet away.

The goals are ambitious. The Fairfax DOT’s first stated goal is to “create Tysons’ focal point,” bringing a sense of civic centrality to a place that has never quite had one.

The Tysons Urban Design Guidelines, though, have a different vision for these thoroughfares, which it envisions as boulevards, saying “above-grade skybridges or below-grade pedestrian tunnels are strongly discouraged as they detract from the vibrancy of the streetscape.” Even with the elevated plaza concept, though, Fairfax DOT would prioritize “connect[ing] ground floor spaces with programmed open spaces.”

Borkowski ended a conversation with Tysons Reporter with the reminder: “This is all very high-level, and nothing has been designed yet.”

Many, many details have not yet been considered, and the possibilities in this article are still nothing more than that: possibilities. Still, the Fairfax DOT does intend to narrow down its options and to move forward in meetings with the Tysons Partnership and other stakeholders within a year.

The February cold might have stopped many comfort-loving Tysonians from hopping on a Capital Bikeshare bike. But some hardy souls still braved the weather last month — 262 times, to be precise.

That number is up 32 percent from last February, when 199 individual trips were made on the Tysons part of the Capital Bikeshare system.

This increase compared to last year indicates that ridership is witnessing a positive overall trend, and that more significant increases in usage are likely in store for the warmer months to come. It’s unclear how much of this increase is due to improved bicycle infrastructure and how much is due simply to people becoming more accustomed to bikeshare in general.

The highest number of bikeshare trips recorded in any month in Tysons over the past year was 410 trips in July 2018.

By far the most commonly-used dock this past month was the one located at the Tysons Corner Metro station, with 103 trips beginning there and 119 ending there. Also popular were the stations at Westpark and Jones Branch Drive and at Park Run and Onyx Drive, which saw 40 to 50 departures and arrivals each.

The least commonly used station was the one at the corner of Westpark Drive and Leesburg Pike, which saw only a single departure and a single arrival throughout the entire month.

Vienna is considering opening Capital Bikeshare stations, and Reston’s system may soon see an expansion.

Information for this story was gathered from the Capital Bikeshare’s open system data.

Nightlife may be one of Tysons’ weak spots, but local music in the area has a long history — and a wide-open future.

The Fairfax scene is very diverse, drawing on artists who are local to the county as well as those from elsewhere in the greater D.C. area.

Emblematic of that diversity is an upcoming performance on Saturday, March 23 at the VFW post in west Falls Church. Six different acts will be playing music — two punk groups, three rappers representing a variety of styles and an indie rock four-piece.

D.C. is famous for its historical punk scene, with names like Fugazi that defined a sound across the entire country — but much of that scene happened on the southern side of the Potomac. Although not all of its current residents are aware, Northern Virginia has a strong tradition of independent music. In the 1980s and ’90s, most of that tradition was being made in Arlington.

The little county was home to the nationally-successful punk group Minor Threat, whose frontman Ian MacKaye later starred in Fugazi, as well as many other bands. It also boasted the Dischord and Teenbeat record labels and the Positive Force activist group, which was closely associated with the “Riot Grrrl” feminist movement.

These groups were often based out of houses, dotted across Arlington. The county was successful musically because it was cheap and offered easy access to the city — but, unfortunately for the punks, the rest of society caught on.

Today, the median home on the Arlington market is listed at over $700,000, and there aren’t many places left in the county for young musicians living on a shoestring budget. In the words of Positive Force co-founder Mark Andersen, “there was another Arlington that existed, and that was a much more humble Arlington.”

In some ways, Fairfax carries on that tradition. By offering (relatively) affordable performance spaces, a large population of potential audiences and a wide network of musical collaborators, the county has a lot to offer a young musician.

There are some major differences, though: today’s scene isn’t only about punk music. Also, it’s less tied to D.C. than it used to be, and has more potential to define itself as “NOVA” music. It does face some obstacles, though, including the drain of talent and attention to nearby cities like Richmond and Baltimore, and, as in Arlington, the difficulty of coexisting with some of the most desirable residential neighborhoods on the East Coast.

To understand what it’s like to record and perform in Fairfax today, Tysons Reporter spoke with Jason Saul, a melodic rapper native to the area.

Tysons Reporter: First, how did you get to be making music in VA? Are you originally from the area? When did you start rapping, and what’s driven you to the style you use?

Jason Saul: I was born & raised in NOVA. I started writing music when I was 13 but it was never anything super serious… Once I turned 20 I realized there wasn’t anything else that brought me the amount of joy that making music does. So now I’m seeking to make music my career. My style comes from influences of music that I listened to when I was young. I’ve always enjoyed storytelling or making music the correlates with the listener. To me, music is all about feeling. Eventually I started to make more melodic music since that’s what I always gravitated towards.

Tysons Reporter: Second, what should I know about the NOVA scene in general? How does it compare to other scenes around the D.C. area — does it have a particular identity compared to, say, D.C. or Maryland? Is it known for particular styles, or for particular venues? Do you want to stay around here, or, if not, where would you go?

Jason Saul: The NOVA scene is very interesting when it comes to music because I see it as a big question mark on the creative map. No one can really say NOVA has a particular sound, and I think that stems from no one really making it out on to the mainstream platform yet. I know there’s Kali Uchis but that’s just one artist. I respect D.C. a lot because it’s so rich with culture but I would definitely separate NOVA from D.C. just because it really feels like two different worlds. MD in my opinion is known for their raw rapping which is great. It’s up to NOVA to see what we come up with now. I’d love to stay here and I probably will but I also enjoy the weather in the west coast.

Tysons Reporter: Third, it’s pretty cool to see this wide a mix of sounds at a single show. Is that standard, would you say, or is this unusual? If it’s unusual, what helped bring it together this time?

Jason Saul: It’s very exciting to see a show like this going down because it’s bringing different groups of people together. I wouldn’t say it’s the ordinary but it’s definitely going to be a good show and should happen more often. What helped bring it together was the relationships some of us have outside of music, just knowing each other really. This gives the audience and artists a great opportunity to discover some music they never thought they’d listen to.

To listen to some of Fairfax’s local musicians, check out these artists, who will be performing at 6:30pm – 11pm on Saturday, March 23, at the VFW Post #9274 (7118 Shreve Road), just 10 minutes from Tysons on Leesburg Pike. There will be a $5 cover charge, and Respawn Thrift will be selling vintage clothing.

Desperry (NoVA, Hip-hop)

Holographic (NoVA, Hardcore punk bootgaze)

Jason Saul (NoVA, Melodic hip-hop)

Needle (D.C., Grind punk)

Wisteria (MD, Indie rock)

Lil Dynamite (NoVA, first show)

Traffic is not inevitable, and new development does not have to bring new cars.

Arlington County saw an astounding decline of 20 percent in average weekday traffic in just 15 years from 2000 to 2015. That same period saw a growth of nearly 20 percent in population. Certainly, many of Arlington’s new residents drove cars — but not all, and some of its long-time residents must have found new ways to get around.

There are several ways to fight congestion. Most people’s first thought is simply to widen the road. More road, more space for cars, less traffic — right? The problem is that it won’t work for long.

For economists, mobility can be a commodity like any other. And when the government gives something away for free — in this case, it’s giving away the use of asphalt — of course people will clog the system. When something is available for free people will wait in line, paying with time instead of money. So, if highway engineers widen the roadway, it’s only a matter of years until more cars come along and the traffic is as bad as it ever was.

Another idea might be to slow down new development — but it would be difficult to persuade Fairfax County to forgo all the additional tax revenue.

Third, the county could turn to public transit. The Metro arrived in Tysons in 2014 and, while ridership is increasing, it still lingers below expectations. It was certainly a step in the right direction, but Metrorail was a major investment, and it will take decades of development and improvements to local bus service and sidewalks before it sees full results.

Wider roads, slowing development, and railways are 20th-century solutions. The 21st century brings a more subtle, smarter approach — an approach that professionals call “transportation demand management.”

Transportation demand management is not a single technique, but a set of approaches that nudge people out of their cars and towards buses, bikes, walking and working remotely. It’s practiced cooperatively by Fairfax County, the Tysons Partnership and private developers. It often relies heavily on data-driven, highly connected approaches rather than on large infrastructure investments.

One example of a transportation demand management program is the “Guaranteed Ride Home” offered by Fairfax County. This program offers commuters a free trip home up to four times every year. It’s intended for those who would consider a new kind of commute, but who the fear of unplanned overtime or family emergency keeps tethered to their cars.

What Developers Are Doing

For a clearer understanding of what individual developers are doing to cut congestion, Tysons Reporter spoke with Caroline Flax of The Meridian Group, the master developer of The Boro.

Flax described the “pedestrian experience” at The Boro, and the options that will be available to people on foot. By locating residences close to offices, retail, restaurants and Metro stations, Meridian hopes to “create a bite-sized pedestrian experience.”

“We will have a pedestrian-only promenade that connects to Boro Park, and for the other streets we have created wide sidewalks with activated outdoor seating that will create a really inviting pedestrian experience,” she said.

According to the EPA, concerned with carbon emissions from cars, “Research consistently shows that neighborhoods that mix land uses, make walking safe and convenient, and are near other development allow residents and workers to drive significantly less.”

“[Transportation demand management] is about promoting the other transit options available to residents, visitors, and tenants — aside from driving,” she said. Those options include bicycles, buses, and trains.

Caroline emphasized “making [The Boro] accessible in general” — including shared office/commercial parking to efficiently accommodate drivers, wide sidewalks for pedestrians, designated bike parking, Capital Bikeshare, and creating options for easy pick up and drop off by ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft. Flax said that she hopes visitors and tenants at The Boro embrace all modes of travel.

Meridian will strengthen its five-minute walking connection to the Metro by supplying new residents with complementary SmarTrip cards, helping them see how easily they can “hop on the Metro and get downtown, or elsewhere in Tysons, really quickly.”

Flax also emphasized the new streets that will help make traffic smoother by creating more options and connections from the main thoroughfares in Tysons: Route 7, Westpark Drive and Greensboro Drive.

Silver Hill Road, connecting from Greensboro Drive to Route 7, is expected to alleviate traffic on Westpark Drive. Another connection, called Broad Street, currently links drivers and pedestrians from Solutions Drive to another new street that connects to Route 7. Once the second phase of the project begins, Broad Street will connect Westpark Drive to Spring Hill Road.

Smaller blocks make a neighborhood more walkable.

Transportation demand management is a field still in its infancy, as planners and developers find new ways to work toward a more balanced transportation network. People across the country are searching for new tools, and Tysons, frequently dubbed “America’s Next Great City,” will have to work hard to be on the cutting edge.

With the Boro opening soon, Flax concluded by saying, “We’re really excited for everything to come alive… and to show everyone the pedestrian experience we will bring.”

Last week, Tysons Reporter examined the importance of sidewalk design as Tysons expands its pedestrian infrastructure network.

But no matter how well-designed a sidewalk might be, what matters most is that it’s in the right place.

There are three guidelines that Tysons can follow to make its pedestrian infrastructure more complete. The first is simply to find where people are already walking. The second is to connect sidewalks to public transit. The third is to provide cut-throughs in large blocks, connecting up the network.

Find the demand

An old architecture-school anecdote mentions a designer who was hired to lay out paths across a new college campus.

For the first months of the year, she left the entire campus unpaved, and students walked across the grass to their classes.

After the first snowfall, she took pictures of the quad from the bell tower, and then laid out the paths wherever she saw footprints in the snow.

In just the same way, dead grass and bootprints in Tysons reveals pedestrian activity. These are called “desire paths.”

They’re useful for transportation planners because they can prove, no speculation needed, that there really is demand for a sidewalk in a particular place. Even Tysons Plaza, connecting the mall to the Metro station, shows desire paths.

Desire paths can easily be paved over by the owner of the land, whether that is Fairfax County, the Virginia Department of Transportation, or a private interest. According to VDOT’s Project Cost Estimating System, a sidewalk costs only $25.15 per linear foot to install in Northern Virginia — it’s hard to think of a more affordable investment in transportation.

You can find desire paths all over Tysons at the ground level, especially near transit stations — which leads us to the next guideline.

Follow the transit

Public transportation and walkability have a symbiotic relationship. Unlike cars, buses and trains rarely drop passengers off right at their destination, meaning that they generally have to walk the final fraction of a mile. But in Tysons, that final stroll can be made circuitous, dangerous or uncomfortable by poor or disconnected pedestrian infrastructure.

As Jeff Speck, author of Walkable City, puts it: “while walkability benefits from good transit, good transit relies absolutely on walkability.” Since its opening in 2014, Silver Line ridership has been less than half of what was anticipated — perhaps because of Tysons’ slower-than-expected transformation into the kind of walkable area promised by ongoing development.

Pedestrian infrastructure is just as important to buses as it is to trains, particularly when a large number of bus stops in Tysons — like one pictured above — are located at neither crosswalks nor sidewalks. Crosswalks, including those in the middle of blocks, are essential to safety; according to VDOT, 51 percent of pedestrian injury crashes occurred at mid-block crossing locations and 86 percent of pedestrian fatal crashes occurred at locations without a marked crosswalk.

Mid-block crossings aren’t new to Fairfax, and they’re approved by VDOT and encouraged by the National Association of City Transportation Officials.

Connect the network

There are two main things that can get in the way of someone walking in Tysons, and they both tend to be larger here than in America’s older cities: streets and buildings.

The single block containing Tysons Corner Center measures almost half a mile, equivalent to about half a dozen blocks of downtown D.C. To walk around Tysons’ ‘superblocks’ is a long journey, but if paths are carved through them, these paths multiply the number of five- or ten-minute trips available to pedestrians.

Similarly, bridges and crosswalks also function as multipliers by connecting sidewalk networks. When a pedestrian bridge connected the Towers Crescent office building to Tysons Corner Center, it not only meant that 3,000 employees could walk to a variety of food options for their lunch hour, taking their cars off the road, it connected them to an expanding network of comfortable pedestrian infrastructure reaching beyond the Metro station.

A successful project

When sidewalks opened last month along Leesburg Pike under the Chain Bridge Road overpass, the project was successful because it observed all three of these guidelines.

First, there was demand. As one reader, Ryan, observed in the comments section, “Commuters were walking in the street for a few years, before we had this new sidewalk.”

Second, it was near transit, adjacent to the Greensboro Metro station.

Third, it provided a link between two previously-disconnected sidewalks, meaning that it didn’t only add pedestrian potential but multiplied it.

More and more sidewalks are coming to Tysons, but not all of them are created equal.

Sidewalks have been getting a lot of attention lately, They’re credited with the power to revitalize the economy and save lives, but sidewalks, like all infrastructure, need planning, engineering and investment — and some are implemented better than others.

Modern designers understand the subtleties of how to make a sidewalk safe and comfortable, while exciting new materials offer new technological possibilities and economists are coming to better understand the investment potential of sidewalks.

The best tools in any arsenal are multitaskers, and sidewalks aren’t just for moving. Just like we use streets for both driving and parking, we use sidewalks both for walking to a destination and also for standing still once we arrive.

In dense residential areas, like The Boro or The Mile, sidewalks can provide an outdoor common space, like a shared living room, for those living in small apartments. Sidewalks are also a good investment — they contribute thousands of dollars to property values. Good sidewalk design can even make a street safer for drivers.

Anatomy of a Sidewalk

The National Association of City Transportation Officials has a lot to say about how to engineer sidewalk space. In its design guide, it carves sidewalks up into three parallel zones – and while all three are for people, only one is actually about walking.

The frontage zone meets the facades of buildings and functions as an extension of them. It is usually home to cafe seating, benches, signs, staircases and entry ramps, and in residential areas individuals’ front gardens.

It can provide small nooks where you can stand under an awning and fire off a text message, or a place for eager customers to wait in line at the hip new cupcake shop. The frontage zone, while public, feels most closely associated with the building it touches.

The through zone is where pedestrians actually travel. It’s a clear lane for foot traffic, extending straight across multiple blocks, free of obstructions and wide enough for wheelchair users or groups of walkers to pass one another. It is often distinguished from the other two zones by a slightly different paving material. In order for pedestrians to move quickly, comfortably and efficiently, the through zone must be wide (at least five feet and up to 12) and unobstructed.

The furniture zone, also called the curb zone, is both the access to and the barrier from the street.

Traditionally, it is home to trees, light posts, traffic signs, utility boxes, newspaper stands and bus stops. In the 21st century, it gives us access to our wealth of new mobility options: car rental kiosks, Capital Bikeshare stations, pick-up zones for Uber or Lyft. This is where shared scooters ought to be parked.

Like the frontage zone, it can have benches or picnic tables, but this space feels entirely public, whereas benches in the frontage zone seem to belong to the adjacent building. The objects, furniture, and especially trees in this zone protect pedestrians from car traffic but the bus stops, taxi stands and bikeshare stations let them enter it on their terms. Like the wall of your house with its doors and windows, it protects you from the elements while also forming a point of access.

All sidewalks have these three zones, although they might blur together or be very narrow. Designing a good sidewalk, though, means understanding the role of each. Many sidewalks in Tysons, for lack in investment, don’t have the essential elements that fully flesh out the frontage and furniture zones. These sidewalks, simple concrete paths through grass, are incomplete.

Sidewalk Engineering

Concrete is classic, but new materials offer exciting possibilities for the sidewalks of the future. New kinds of sidewalks could double as automatic storm drains, use recycled materials, or generate electricity — and the D.C. area is on the cutting edge.

Engineers in many cities around the world have started experimenting with using recycled rubber as a paving material for the last two decades. Results have been mixed, with maintenance costs higher than expected in some places, but the rubber has a threefold advantage. DC has been a national leader with this technology, meaning Tysons has a lot of local expertise to reference.

First, by reusing waste rubber, the material is ecologically friendly.

Second, this rubber paving is usually slightly porous — meaning it absorbs some water during a heavy rainfall, helping deal with the thorny problem of stormwater management and preventing puddles from accumulating.

Third, as trees on sidewalks grow, their roots can push up and out, dislodging cement blocks and making the through zone inaccessible to those in wheelchairs. Rubber paving, because of its flexibility, can actually accommodate shifts in root structures without cracking.

Another new type of sidewalk has only made its way out of the laboratory a few years ago. In 2013, the George Washington University campus in next-door Loudoun County unveiled the world’s first walkable solar-powered pavement. This “Solar Walk,” part of the public campus sidewalk, uses solar panels embedded beneath a reinforced material to generate electricity that can not only light the sidewalk up at night but also send some power back to nearby Innovation Hall.

However, these flashy technologies have their critics, and it may be that traditional bricks offer greater value and some of the same benefits as the rubber material.